A large international genetic study adds to growing evidence that many mental health conditions share common genetic risks rather than having distinct biological origins. Analysing genetic data from more than one million individuals across 14 psychiatric and neurodevelopmental conditions, the researchers found that inherited risk clusters into a small number of broad genetic dimensions.

The study examined millions of common genetic variants associated with conditions including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anorexia nervosa, and substance use disorders. Instead of identifying disorder-specific genes, the analysis focused on shared genetic patterns across diagnoses.

Five major genetic factors emerged, together accounting for about two-thirds of the shared genetic risk captured by common variants. These were described as compulsive, schizophrenia–bipolar, neurodevelopmental, internalising, and substance use factors. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder showed particularly strong genetic overlap and were grouped into a single factor, reflecting long-recognised clinical similarities.

What it means clinically

Nidhi Shah, medical geneticist and senior scientific advisor at the Neuberg Centre for Genomic Medicine, said the findings do not suggest the existence of a single gene responsible for mental illness. “These are polygenic risks. Many common genetic variants, each with a very small effect, together increase vulnerability. They increase risk, not certainty,” she said.

Clinically, this means that individuals who carry a genetic risk for one mental health condition may also be biologically vulnerable to other conditions within the same genetic group. Whether this risk translates into illness depends on multiple factors, including environment, stress exposure, trauma, sleep, and access to care.

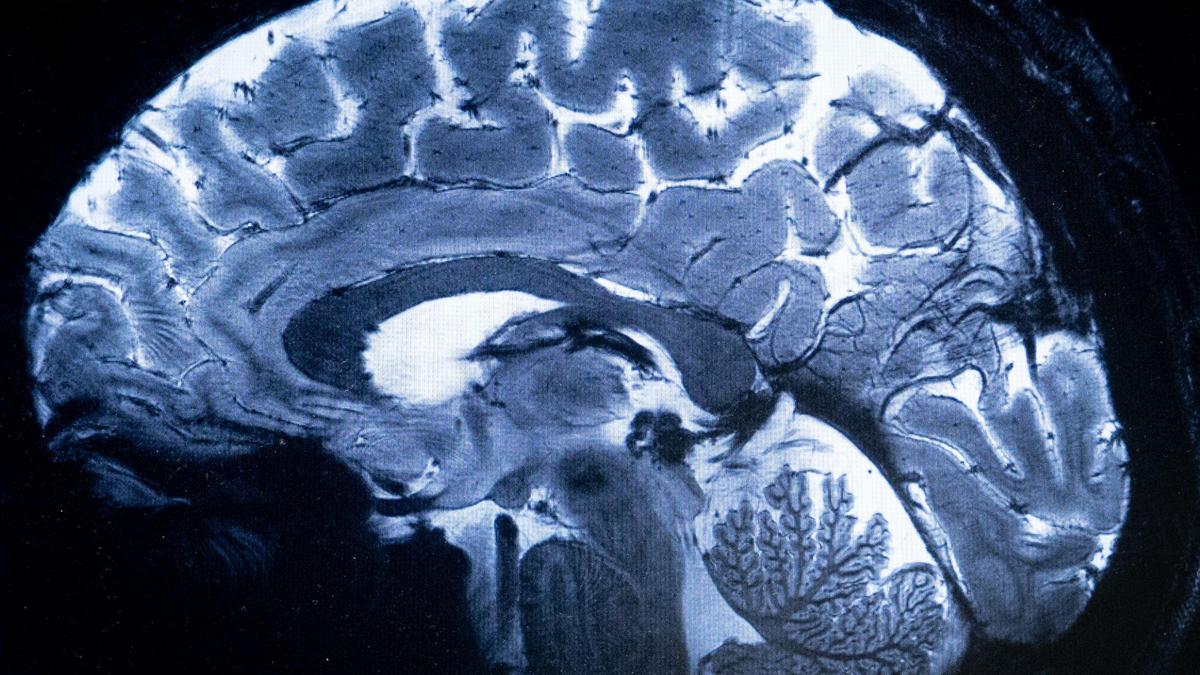

The study found that shared genetic risk was concentrated in genes active during early brain development, particularly during foetal and early postnatal stages. These periods are critical for neuronal migration — developmental process where newborn neurons travel from where they’re born to their final, specific locations in the brain, synaptic development –process where neurons form connections (synapses) and refine them for efficient brain function , and the formation of brain networks involved in cognition, emotional regulation, and stress response.

Sheffali Gulati, child neurologist, department of paediatrics, AIIMS New Delhi said this is consistent with current neurodevelopmental understanding. “Disruptions during early brain development can have long-term effects on emotional regulation and behaviour. Circuits linking the prefrontal cortex (the front part of the brain) and limbic system (system of nerves and networks in the brain) appear especially sensitive to these shared genetic influences,” she said.

Different clinical conditions may therefore emerge from overlapping developmental pathways, shaped by timing, brain regions involved, and environmental influences.

Overlapping symptoms and diagnoses

The analysis also showed that genetic risk is expressed differently across brain cell types. The schizophrenia–bipolar factor was enriched in genes active in excitatory neurons — nerve cells that promote the firing of an electrical signal in the next neuron, while internalising conditions such as anxiety and depression were more strongly linked to glial cells and oligodendrocytes, which play a role in brain connectivity and stress regulation.

These findings help explain how disorders with distinct clinical features can arise from partially shared biological mechanisms.

The study offers a biological explanation for the high rates of comorbidity seen in clinical practice. Children and adults frequently meet criteria for more than one mental health condition, and diagnoses often change over time. ADHD commonly co-occurs with anxiety or mood disorders, while autism often overlaps with ADHD and anxiety.

Dr. Shah said such patterns should not be viewed as diagnostic error. “Shared genetic liability likely explains why overlapping symptoms and multiple diagnoses are so common,” she said.

Dr. Shefali added that this supports a developmental view of mental illness rather than seeing conditions as fixed and isolated.

Diagnosis and care

Current psychiatric diagnoses remain central to clinical care and service delivery. They are based on symptom patterns and functional impairment and continue to guide treatment decisions. However, the findings suggest that these categories may not fully reflect underlying biology.

The identification of broad genetic dimensions supports a more dimensional view of mental illness, where conditions exist on overlapping spectra. This does not invalidate existing diagnoses but highlights their biological limits.

Prabash Prabhakaran, director and senior consultant, neurology, SIMS Hospital, Chennai, said the findings reinforce a shift toward a more dimensional, transdiagnostic understanding of mental illness in clinical practice. He noted that a family history of any serious mental illness often signals elevated vulnerability across a range of conditions including mood, psychotic, anxiety, and neurodevelopmental disorders rather than risk confined to a single diagnosis.

In clinical counselling, this shifts emphasis away from rigid categorical predictions toward broader susceptibility, shaped by brain development, environmental exposures, stress, trauma, sleep, and access to care. For clinicians, Dr. Prabhakaran said, psychiatric diagnoses should be viewed as working constructs, essential for communication and treatment planning, but requiring flexibility as symptom profiles change across the life course.

He added that overlapping genetic risk suggests early childhood emotional, behavioural, or attentional difficulties may represent vulnerability to multiple later trajectories, underscoring the importance of longitudinal monitoring and early, broad-based interventions rather than narrowly diagnosis-specific approaches. There is also evidence of shared genetic risk between psychiatric conditions and some neurological and somatic disorders, he said, supporting partially shared pathobiology across brain-based illnesses and the need for closer integration between psychiatry, neurology, and general medicine.

In the near term, mental health care is expected to remain diagnosis- and symptom-based. Treatment decisions must continue to address what patients are experiencing, including mood symptoms, psychosis, anxiety, attention difficulties, substance use, sleep problems, and safety concerns.

Over time, shared genetic insights may support treatments that target biological pathways common to multiple conditions. This could allow therapies developed for one disorder to be used across related conditions and encourage wider use of transdiagnostic approaches.

Limits and cautions

The experts cautioned against premature clinical use of genetic findings. Current polygenic risk scores are not accurate enough for individual screening and perform differently across populations.

A major limitation is ancestry bias. Most large genetic datasets are drawn from individuals of European ancestry, limiting the applicability of findings to populations such as those in India. Genetic overlap between conditions is known to vary across ancestral groups.

Shared genetic risk reflects probability, not inevitability, and does not reduce the importance of psychosocial factors, education, therapy, and social support. There is also a risk of stigma if genetic overlap is misunderstood or overinterpreted.

Experts emphasise that for clinicians, genetics should inform but not replace comprehensive clinical assessment. Ethical use requires protecting privacy and avoiding genetic determinism.

Implications ahead

For patients and families, the findings offer context rather than prediction. Multiple diagnoses are common and biologically plausible. Family history matters, but it does not determine outcomes. Early support and sustained care can alter trajectories.

For health systems, the study highlights the need for integrated services that can manage overlapping conditions. Closer coordination between mental health and substance use services, continuity of care, and long-term follow-up are particularly important.

At a practical level, the focus of care remains reducing suffering and improving function. Addressing symptoms such as sleep disturbance, anxiety, mood instability, trauma-related symptoms, and cognitive difficulties can improve outcomes even when diagnoses overlap.

As Dr. Shefali noted, genetics adds to understanding but does not replace clinical judgement. The emphasis, she said, must remain on treating the person rather than the diagnostic label.