India’s renewable-energy IPO wave in recent months has largely been dominated by companies such as Vikram Solar, Saatvik Green and Emmvee that make solar modules and supply them to power developers or EPC contractors. Fujiyama Power Systems, whose ₹828-crore public issue opened on November 13 and shall close on November 17, is less of a solar manufacturer and more of an emerging consumer-energy brand. That distinction matters, as it is a retailer in the distributed-energy market which is an ecosystem that straddles consumer electronics, batteries, and rooftop solar installations. Understanding that difference is essential before interpreting its financials or valuation.

The IPO is a combination of fresh issue of 2.63 crore shares aggregating to ₹600 crore and offer for sale of 1 crore shares by promoters aggregating to ₹228 crores. Fujiyama plans to use ₹275 crore of IPO proceeds to repay debt (₹433 crore Q1FY26), and ₹180 crore for the Ratlam facility. Promoters are diluting around 11.8 per cent of their stake. The IPO was subscribed 9 per cent on Day-1.

The IPO prices Fujiyama at 45 times its FY25 earnings, which is cheaper than consumer energy names such as Havells (63x) and Servotech Renewable (69x), but more expensive than the likes of Amara Raja Energy & Mobility (23x) and Oswal Pumps (26x). None of the peers, however, offer an apple-to-apple comparison due to different product portfolios.

Fujiyama’s IPO is better approached with caution. Its recent earnings don’t yet prove a sustained step-up, and investors need more quarters to see whether margins hold once the subsidy-driven rooftop cycle normalises. The business of this small-cap is also exposed to concentration risk, with over 40 per cent of retail sales coming from Uttar Pradesh, and to supply-chain volatility given its continued reliance on imported cells, semiconductors, and lithium-ion components. Brand distinctiveness remains untested in a segment dominated by stronger incumbents, while rooftop demand itself is policy-sensitive and could soften if subsidies or net-metering rules change. These factors argue for a wait-and-watch stance until performance stabilises.

Business

Fujiyama Power Systems manufactures and sells a mix of solar panels, inverters, batteries, UPS systems, E-rickshaw chargers and lithium-ion batteries. They are marketed under its two brands: UTL Solar and Fujiyama Solar. Together, they account for more than 522 stock-keeping units. It has a distribution network of 725 distributors, 5,546 dealers and 1,100 exclusive “Shoppe” franchisee. Panels and batteries together form about two-thirds of total revenue. The solar UPS/inverter segment adds another quarter. E-rickshaw chargers and online UPS lines remain small but growing.

As of June 2025, it operated four manufacturing facilities: Parwanoo (UPS system and solar power conditioning units a.k.a PCUs), Greater Noida (solar panels, inverters, e-rickshaw chargers, lithium-ion batteries), Bawal (panels, tubular batteries), and Dadri (panels). Cumulative installed capacities expanded sharply between FY23 and June 2025, with solar PCU and UPS capacity now 325 MW, solar inverters 1,084 MW, solar panels 1,039 MW, lithium-ion batteries 545 MWh, tubular batteries 1,318 MWh, and E-rickshaw chargers 334 MW.

The business is structurally different from upstream solar manufacturers like Waaree or Premier Energies. About 94 per cent of Fujiyama’s revenue in Q1 FY26 came from B2C channel. The company’s success depends more on brand pull, dealer margins, and consumer financing than on silicon prices or utility-scale tenders. This channel-heavy model explains both its strong reach and its working-capital intensity.

Rooftop-solar market

Fujiyama’s IPO timing coincides with an inflection point in India’s rooftop solar market. According to the CARE Advisory report commissioned by the firm, rooftop installations are expected to grow at 40 per cent CAGR from FY25 to FY30, expanding from 17 GW to nearly 100 GW. In FY19-25 period, it grew 45 per cent CAGR. The boom is being driven by central programmes such as the PM Suryaghar Muft Bijli Yojana, which aims to subsidise rooftop panels for 1 crore households, and state-level incentives.

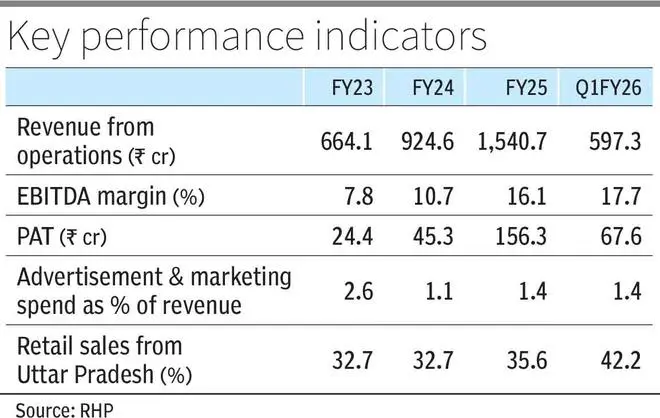

The company’s business is concentrated in North and West India, with Uttar Pradesh accounting for 42 per cent of retail sales in Q1FY26. Top-5 states (UP, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Punjab and Haryana) account for 77 per cent.

Future expansion i.e. the ₹180 crore Ratlam project in Madhya Pradesh, will give it a central-India manufacturing base. The facility is designed to add 2 GW each of panel and inverter capacity and 2 GWh of lithium-battery capacity. That could significantly increase overall output once operational in next 2-3 years.

However, the rooftop segment is also the most operationally complex corner of solar energy. Installation can be small, customer approvals are slow, and sales cycles are long. This means higher overheads and cash-flow delays compared with utility-scale projects. Any policy change in net-metering (credits solar energy system owners for the electricity they add to the grid) or subsidy disbursement can also immediately affect retail demand.

Under the PM Surya Ghar programme, the central subsidy is meaningful. As per RHP, homeowners get ₹30,000 per kW for the first 2 kW and ₹18,000 per kW for the next 1 kW, with the total payout capped at ₹78,000 for systems above 3 kW. Housing societies and RWAs are eligible for ₹18,000 per kW for common facilities (including EV-charging loads) up to defined limits, while certain “special states” receive an additional 10% subsidy. These incentives materially lower upfront costs and improve payback periods, though they are still contingent on MNRE compliance and state-level processes. This makes subsidy flow and approval timelines a key variable for actual consumer uptake.

In FY25, Fujiyama had roughly 15.5 per cent share of the Indian solar-battery market and supplied 1.64 GW of solar inverters, accounting for about 9.6 per cent of inverter capacity. These categories command higher margins and customer stickiness because they are branded purchases, not commodities. Consumers identify with inverter or battery brands, not the module supplier. In that sense, Fujiyama competes less with Waaree or Adani Solar and more with Luminous, Microtek, Exide, and Amara Raja Energy & Mobility.

To sustain visibility, such business models rely heavily on dealer commissions and franchise incentives. Advertising and marketing expenses at 1.4 per cent of revenue in FY25 has grown YoY, but remains low compared with the 3–5 per cent spends typical of established consumer-durable players. Fujiyama may have built a retail-facing model, but its brand investment still reflects a manufacturer’s caution rather than a marketer’s aggression. Maintaining visibility on such lean budgets could test the limits of its current franchise model and its ability to hold premium pricing, once growth normalises.

Financials

The aggressive scaling underlines why revenue more than doubled over two years from ₹664.1 crore in FY23 to ₹1,540.7 crore in FY25, with a further ₹597.3 crore in the June-quarter FY26 alone. Profit after tax rose over six-fold from ₹24.4 crore in FY23 to ₹156.3 crore in FY25, and ₹67.6 crore in Q1 FY26, a trajectory few industrial peers can match. EBITDA margin climbed to 16.1 per cent in FY25 and 17.7 per cent in Q1 FY26, from 8-11 per cent in FY23-24.

We believe the above may not represent steady-state growth. Such rapid expansion coincides with a period of extraordinary industry profitability when module and cell prices softened sharply while end-consumer pricing remained firm. FY25 return on equity of 39.4 per cent and return on capital employed of 41 per cent are excellent by any standard, though partly reflecting cyclical margin peaks.

Working capital remains the key vulnerability. Net working capital rose to ₹115.2 crore in FY25 from ₹42 crore in FY24, funded largely by short-term debt that increased from ₹137 crore to ₹257.8 crore. Liquidity stayed thin with minimal cash balances. Although reported profits expanded, the OCF/PAT trend is volatile—from very strong conversion in FY23 and FY24 (312% and 189%) to only 12% in FY25, before slipping to –6.7% in Q1 FY26. The recent outflow likely reflects higher inventory and extended credit to distributors, but the broader pattern shows that earnings quality is tightly linked to working-capital swings, and not yet on a stable footing.

Valuation and risks

The IPO prices Fujiyama at 45 times its FY25 earnings, which is cheaper than consumer energy names such as Havells (63x) and Servotech Renewable (69x), but more expensive than the likes of Amara Raja Energy & Mobility (23x) and Oswal Pumps (26x). Though Fujiyama earnings have been robust for Q1FY26, valuation based on annualising as one quarter is not a reliable indicator of full-year earnings.

Fujiyama’s worth will hinge on its ability to convert brand recall into recurring domestic demand. For investors, the key variable is earnings sustainability of this small-cap company. If growth continues without working-capital blow-outs, valuation could look conservative in hindsight. It could emerge as one of the large-scale consumer-solar brands, akin to how Voltas or Havells scaled in cooling and electricals. If not, it risks the fate of earlier inverter-UPS brands that lost ground to larger conglomerates once the market matured.

Despite being positioned as a domestic manufacturer, Fujiyama remains reliant on imported components. About 26 per cent of total purchases in FY25 and 29 per cent in Q1 FY26 were imported, mainly solar cells, semiconductors, and lithium-ion cells from China. This exposure is both a cost advantage and a strategic risk. A planned solar cell plant at Dadri facility may reduce import dependence marginally, but the shift will take time and capital.

Unlike an EPC firm, Fujiyama’s business revolves around its brands “UTL Solar” and “Fujiyama Solar.” The RHP lists three trademarks, four design registrations, and one patent—for its proprietary “rMPPT” energy-harvesting technology. However, the brand “Fujiyama” is not unique globally and could face challenges from unrelated entities. Maintaining brand perception in a category crowded by multi-nationals like Luminous and Havells will require steady marketing outlay, robust after-sales service, and dealer discipline.

The rooftop solar market is heavily policy-driven. Fujiyama and its customers benefit from central and state subsidies that lower effective costs. If subsidy disbursals are delayed or reduced, project economics for end-users could weaken, hurting demand. Similarly, rooftop-solar economics depend on net-metering regulations, which vary across states. Any tightening of these rules could reduce consumer uptake. We believe right now rooftop growth is subsidy-driven, not price-elastic demand.

Published on November 13, 2025