With only a couple of weeks left before the Finance Minister tables the next Union Budget, the aggregate markers of macroeconomic comfort in India’s growth story may appear to be in place, where average economic growth remains strong in relative comparison to global standards, even amid the heightened uncertainty afflicting most other nations.

Yet this story of projected confidence rests on a partial reading of the aggregate data, which veils a deeper, more unsettling reality in India’s economic fundamentals and their governing dynamics. A closer look at recent household finances data suggests that India’s growth is increasingly being underwritten by households that are, on average, saving much less and borrowing more, while quietly absorbing economic risks that were once shared more broadly. This can, of course, increase household debt, especially among vulnerable and low-income groups, who haven’t really gained in employment opportunities or higher incomes over the last few years.

A misleading comfort

The Reserve Bank of India’s Financial Stability Report (December 2025), read alongside its Annual Report 2024-25 and recent Budget documents, points to a shift that deserves attention precisely because it does not yet resemble a crisis, but exhibits enough to merit a red flag.

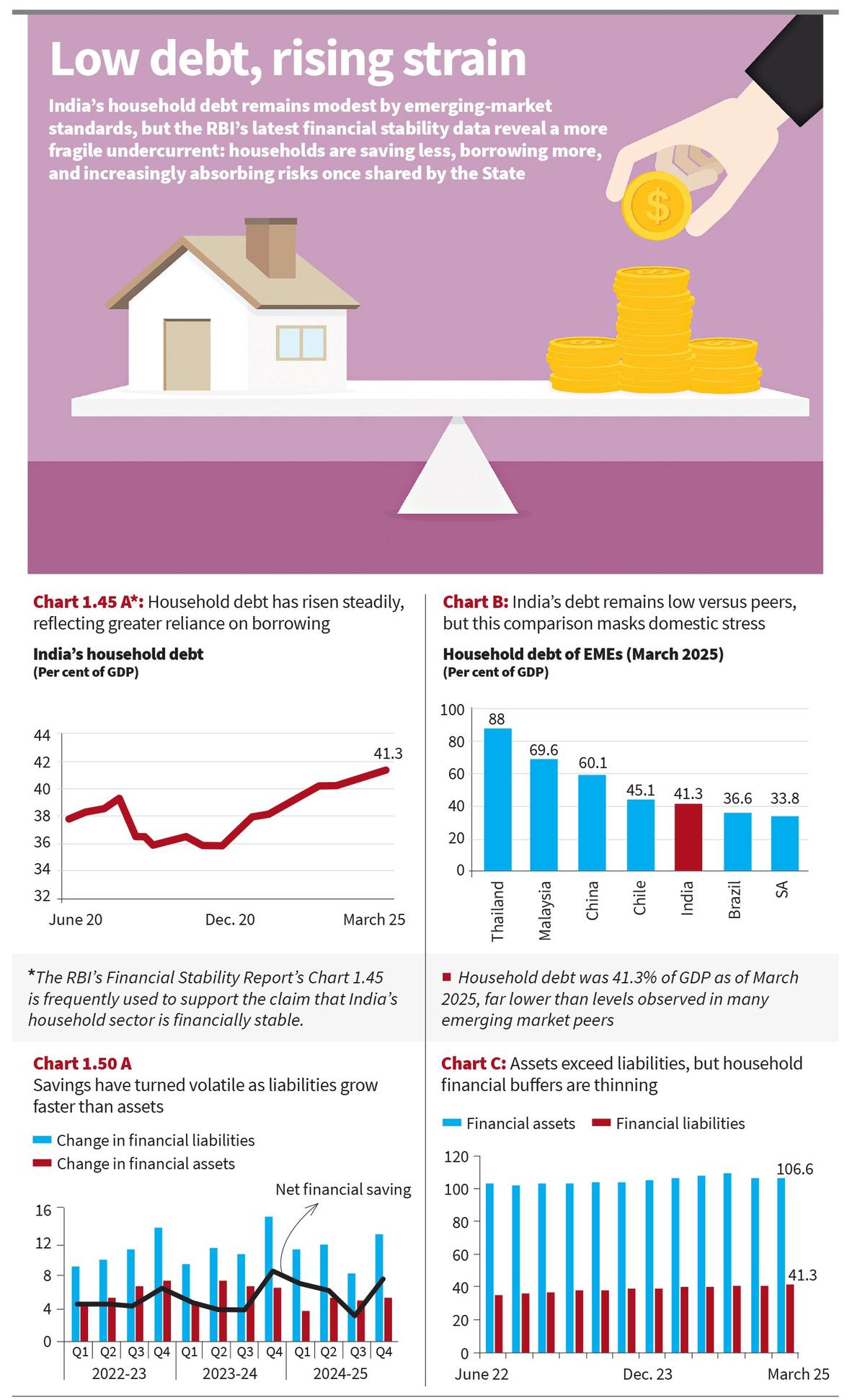

Chart 1.45 of the Financial Stability Report is frequently used to support the claim that India’s household sector remains financially stable. Household debt stood at 41.3% of GDP as of March 2025, far lower than levels observed in many emerging market peers, including China, Malaysia, and Thailand. Additionally, the increase has been relatively gradual rather than abrupt, rising from roughly 36% of GDP in mid-2021 to slightly over 41% by early 2025. It proves that there is no household debt crisis in the traditional sense in India. Excessive leverage or an imminent threat to financial stability is not evident.

However, there are limits to this assurance. Debt-to-GDP ratios demonstrate the extent of household borrowing in relation to the economy, but they do not explain why households are taking on debt or whether they will be able to pay it off over time.

In the present situation, that distinction is important. According to the RBI’s Annual Report 2024–25, real income growth has been uneven, especially outside formal employment and high-productivity sectors. In the meantime, overall consumption has held up well. Households must make other adjustments when consumption holds up despite weak or uneven income growth. Borrowing has become a more common way to make that adjustment.

Credit as a cushion

In this way, a change in the function of credit itself is reflected in the increase in household debt. Borrowing is being used more to close income and expense gaps than to finance the creation of assets. Even moderate debt levels can become a source of vulnerability when they substitute for income growth and savings rather than complement them. That question depends not on how much households owe today, but on how debt, income, and savings are evolving together, an issue that becomes central to assessing the economy ahead of the Budget.

Both sides of the balance sheet are simultaneously captured in Chart 1.50. Financial liabilities accounted for 41.3% of GDP in March 2025, while gross household financial assets stood at 106.6% of GDP. There is no indication that liabilities have surpassed assets, and households continue to be net holders of financial wealth. It is simple to conclude that household finances are sound based only on this.

Examining the flow data is the only way to see the stress. In recent quarters, net financial savings have drastically fluctuated and decreased. Net financial savings recovered to 7.6% of GDP in the last quarter of 2024-25, but this came after a compression to about 3-4% of GDP in the preceding quarter. The quicker accumulation of financial liabilities compared to financial assets is the direct cause of this volatility, according to the RBI.

There are obvious ramifications to this pattern. It indicates a more concerning change in domestic behaviour. Although households continue to save, a growing portion of that savings is being offset by new borrowing.

As a result, headline financial wealth can continue growing while the buffer that shields households from job shocks, income losses, and rising interest rates gradually deteriorates. A growing fragility lies beneath what appears stable in aggregate.

Why households are borrowing more

A more comprehensive fiscal and policy configuration that systematically transfers risk from the State to households is the cause of the increase in household borrowing. According to the RBI’s State Finances: A Study of Budgets 2024–25, State governments have prioritised capital expenditure while limiting revenue expenditure.

Committed expenditures — interest payments, pensions, and salaries — now account for between 30 and 32% of State revenue receipts, leaving little space for income support or countercyclical transfers. States have actually become less responsive to household income stress while also becoming fiscally leaner.

At the Union level, the Budget at a Glance 2025-26 shows a continued emphasis on public investment, with capital expenditure budgeted at ₹11.2 lakh crore and effective capital expenditure at ₹15.5 lakh crore. This strategy is growth-enhancing, but it is not household-neutral. Infrastructure investment raises medium-term potential, yet does little to smooth short-term income volatility.

The result is a quiet reallocation of risk. As governments consolidate and invest, households are asked implicitly to insure themselves.

A macro risk hiding in plain sight

This shift matters because it changes the very character of India’s growth. Private consumption accounts for close to 60% of GDP, making household spending the economy’s primary stabiliser. The danger lies in the interaction of three trends documented across the RBI’s recent reports.

First, the Annual Report 2024-25 notes that real income growth has been uneven, especially outside formal employment and high-productivity sectors. Second, while borrower risk profiles have improved, unsecured retail credit has expanded rapidly, indicating that consumption is being sustained on thinner financial cushions. Third, as shown in Chart 1.50, net financial savings have become volatile and, at times, sharply compressed, as liability accumulation increasingly offsets asset formation.

A slowdown in income growth, a tightening of financial conditions, or a rise in unemployment would reduce discretionary spending and, more critically, compel households to retrench abruptly, because debt-financed consumption offers little room for adjustment.

Union Budget 2026 will be framed understandably as a continuation of macroeconomic stability achieved through fiscal discipline and investment-led growth. However, stability that depends on households taking out loans to maintain demand is not self-sustaining and merits a closer look at options which can enable disposable income for households.

It is not guaranteed even then that any marginal increase in income can help increase savings but may at least catalyse that over time in the longer term, while helping the citizenry take care of debt interest or borrowing repayments in the short to medium term. Restoring balance in the household budgeting calculus is the key fiscal policy-task prior to Budget 2026. Creating demand, more labour-intensive employment, and aligning fiscal outcomes towards these, while increasing average incomes, will eventually be affected by an economy where households gradually lose their ability to absorb shocks.

Deepanshu Mohan is professor and dean, O.P. Jindal Global University and Director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES). He is a visiting professor at LSE and a visiting fellow at University of Oxford. Geetaali Malhotra contributed to this column