For most of my adult life, I’ve felt helpless about being overweight. When I met with a doctor a few years ago to discuss my high cholesterol, he held up a hunk of faux flesh meant to model a pound of excess fat and encouraged me to lose 20 of said gelatinous blobs. Perhaps, he suggested, I should eat less red meat and start exercising. I still remember his perplexed stare after I told him I had an established gym routine and had been a vegetarian for the better part of a decade.

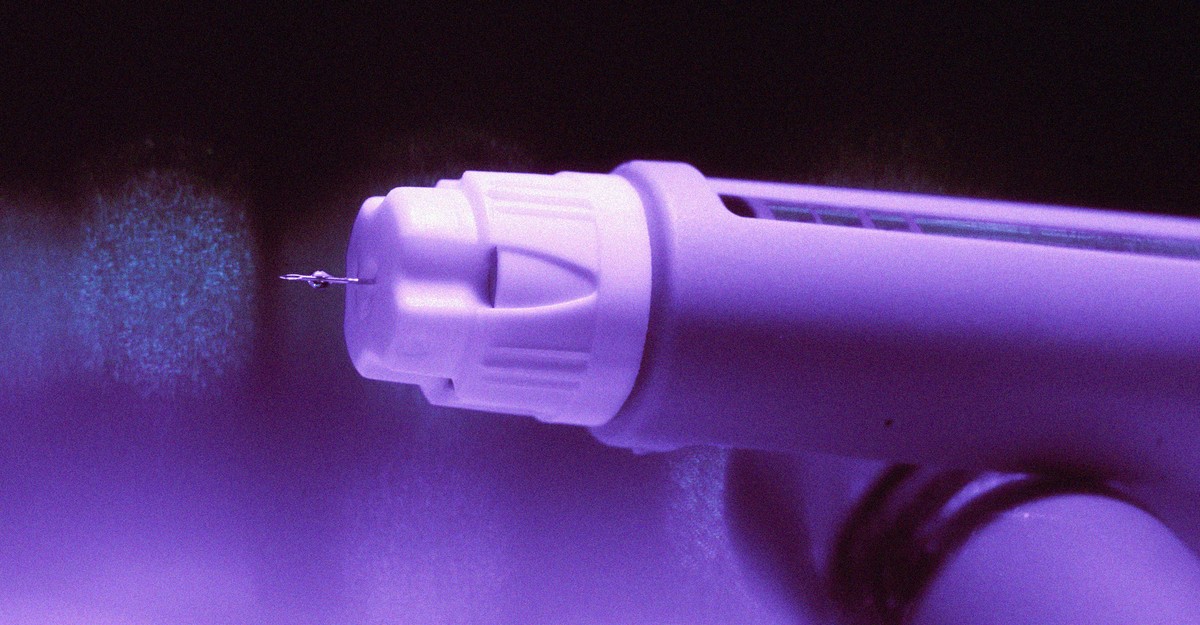

Starting an obesity drug was supposed to be triumphant. The days of being winded after walking up the stairs to my apartment, and buying T-shirts marketed for guys with big bellies, would finally be over. Or so I thought. My health insurance didn’t cover Wegovy or Zepbound, the two GLP-1 drugs approved for weight loss. (Both medications are also sold for diabetes, under the brand names Ozempic and Mounjaro, respectively.) Despite my pleading, the insurance company wouldn’t budge.

For all the hype over GLP-1s, Americans have struggled to access these weekly injections. Seniors can’t get these drugs because Medicare is barred by law from covering them for obesity. Drugmakers previously couldn’t make enough of the drugs to keep up with demand, prompting the FDA to formally declare a shortage. The supply issues have now abated, but getting these drugs has somehow become even harder. The problem is that insurance companies are refusing to cover them.

Consider Zepbound, the more effective GLP-1 for weight loss. More than half of all private insurance plans do not cover Zepbound at all, up from 18 percent last year. That’s according to recent data from GoodRx, a site that compares prescription-drug prices. Plans are more likely to cover Wegovy, according to GoodRx, but a dwindling share let you get the drug without first going through barriers that may end up curtailing access.

Eli Lilly, the pharmaceutical company that makes Zepbound, blames the lack of coverage on the stigma of obesity. “Despite obesity being recognized as a chronic, complex disease, insurance and federal programs still do not provide broad coverage to people who live with this disease,” the company wrote in a statement. But that isn’t the full story. Many Americans get health insurance through their job, and GLP-1s are so expensive that many companies simply can’t afford the drugs. It might feel like magic when insurance picks up the tab for your prescriptions, but part of those cost savings are actually paid by your employer. A month’s supply of a GLP-1 retails for at least $1,000. When you consider that roughly three-quarters of American adults are overweight or obese, employers could be faced with hundreds or even thousands of GLP-1 bills each month. (Americans who are overweight but not obese are eligible for GLP-1s if they have high cholesterol or certain other health conditions.) “It’s brutal, and it’s forcing employers to make tough decisions,” James Gelfand, the president of the ERISA Industry Committee, a lobbying group that advises large employers on health-insurance issues, told me.

[Read: Ozempic or bust]

For companies looking to manage the costs, “the solution to the problem is just making it more difficult to get the drugs,” Ameet Sarpatwari, a drug-pricing expert at Harvard, told me. Smaller companies are especially struggling; a survey released last week by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that just 16 percent of employers with 200 to 999 employees are covering Wegovy or Zepbound, compared with 43 percent of employers that have 5,000 or more employees. But even major corporations are making patients go through hurdles before they can access these drugs. One of the most common policies requires doctors to submit additional paperwork explaining why a patient needs these drugs before a prescription can be picked up. That might not sound all that onerous, but peer-reviewed research shows it delays patients from getting the drugs their doctors say they need. In my experience, it also requires sustained effort from the patient to corral a doctor’s office into submitting the necessary paperwork.

If employers need to put restrictions on the GLP-1s patients can access, it would seem logical that they would start with Wegovy. Notably, the drug costs about $300 more a month than Zepbound—and it also works less well. (A head-to-head trial of the two medications, funded by Eli Lilly, found that patients on Zepbound lost an average of 20 percent of their weight, versus about 14 percent for those on Wegovy.) Nevertheless, it’s much harder to get Zepbound than Wegovy. “You can’t assume that just being the best product means that you’ll be on the formulary,” Gelfand said.

Insurers are basing their coverage decisions, in part, on “rebates,” discounts that are offered by drugmakers as a negotiating chip to persuade insurers to cover one product over a competitor. For example, in July, CVS Caremark, a pharmacy-benefit manager hired by insurance companies to help determine which drugs to cover, began recommending Wegovy over Zepbound in most cases. Ed DeVaney, the president of CVS Caremark, told me that the decision was made because his company deemed the two drugs very similar in terms of efficacy, and because the deal represented “the highest value” for the health plans and employers the company works for. But the move hasn’t been popular. Doctors favor Zepbound over Wegovy, according to prescribing data analyzed by the analytics firm Truveta. Prescriptions may go unfilled once patients realize that their insurance companies won’t foot the bill. (CVS Caremark is facing a class-action lawsuit filed by customers who were prescribed Zepbound but weren’t able to get it through their insurance. )

Without insurance coverage, patients have to turn elsewhere for these drugs. Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk sell their drugs to patients directly for a major discount, but they still are prohibitively expensive: A vial of Zepbound costs $500 a month when purchased straight from the manufacturer. Patients can opt for cheaper versions of these drugs that are made by compounding pharmacies, but they can be unreliable and unsafe. Neither of these alternatives were solutions for me, and they likely won’t be for many Americans. Although I tried a few months of compounded drugs, the risks of injecting myself with a serum that hadn’t been reviewed for safety by the FDA started to weigh on me. Ultimately, I was able to get on my fiancée’s insurance, and now I finally have access to Wegovy. (Her plan refuses to cover Zepbound.) But very few patients can turn to this sort of backup plan when their own insurance comes up short.

GLP-1s are hardly perfect. They come with sometimes severe side effects, including nausea, and the weight-loss results last only as long as people keep taking them. But the upside for people with obesity is undeniable. Eventually, millions of Americans who are waiting for these drugs should be able to get them. More competition should lead to modestly larger rebates, making it cheaper for employers to cover these drugs, Sarpatwari said. Novo Nordisk is developing a new obesity drug that clinical trials suggest rivals Zepbound in effectiveness, and Eli Lilly is testing a drug that could end up being even more effective than the current products on the market. Several companies, including Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, are also developing oral versions of these drugs for those who do not want to inject themselves weekly. The new drugs will almost certainly be more expensive than those already on the market, but they should make it slightly easier for patients to access older GLP-1 drugs.

That future remains far away. The start of the GLP-1 era focused on the exciting transformations patients have made on these drugs. If something doesn’t change, the next few years are going to focus on all the people who could benefit from GLP-1s but are unable to access them.