To protect gains in our portfolios, we all need to periodically book profits on outperforming assets and add to underperforming ones. However, this is easier said than done. Behaviourally, who would like to replace stocks which are galloping, with slow-moving bonds?

Sticking to an asset-allocation plan, with periodic rebalancing helps you cut out the emotions that stop you from doing the right thing. You start with a pre-decided allocation between assets. If the weight of an asset shoots up due to price gains, you sell it and buy the other one, until the original allocation is restored.

But does rebalancing work in the Indian context? How often should you do it? What about capital gains tax? We ran a real-life analysis to answer these questions.

What we did

To check out how rebalancing works in India, we initiated a mythical portfolio of ₹1 lakh with a 50-50 allocation between equities and debt on January 1, 1999. We studied how this portfolio behaved over the next 12 years. We assumed that the equity part of was invested in the Nifty50 Total Return Index. The debt portion was invested in a one-year bank fixed deposit (rates sourced from RBI data) at the beginning of every year.

Why did we choose 1999? Indian stock markets have seen high returns and low volatility in the last decade. The coming years could see more dips and crashes. The primary purpose of asset allocation is to smooth out returns. The period from 1999 to 2011 represented a very bumpy period for the Indian stock market, with a rate cycle also playing out.

No rebalancing

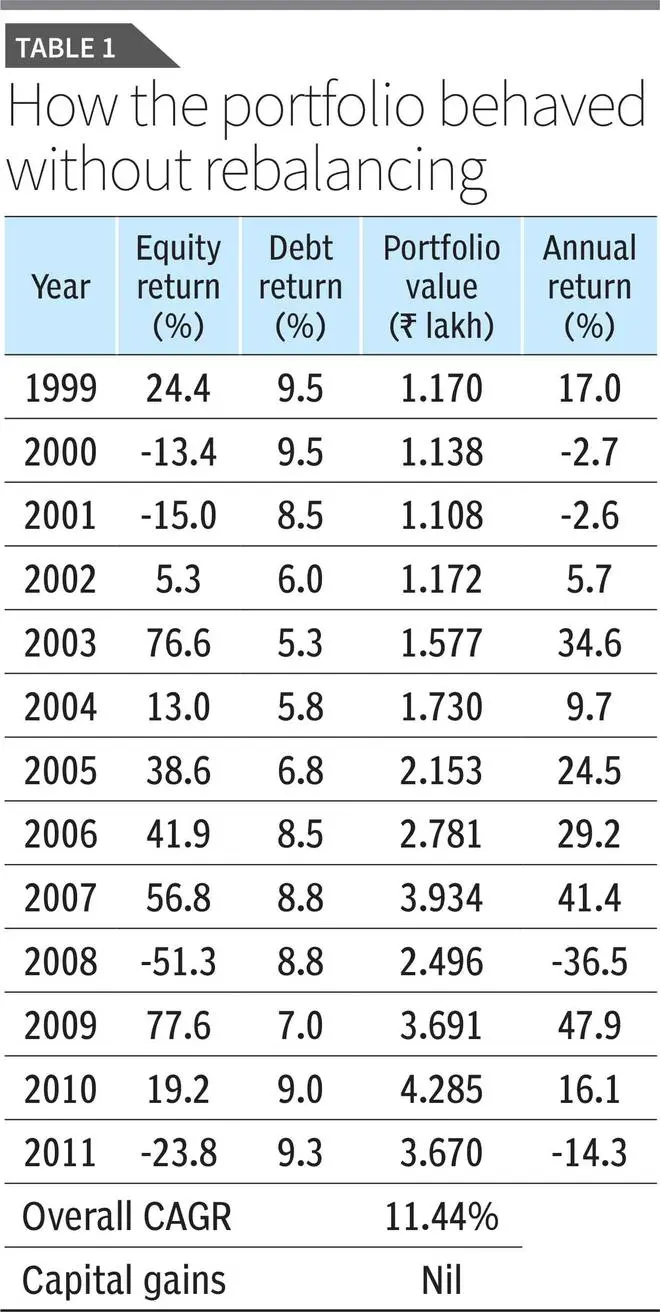

Let’s assume you started with ₹1 lakh split equally between the Nifty50 and a bank FD on January 1, 1999. You sat on your hands thereafter, not tinkering with the allocations. The journey of this portfolio is presented in Table 1.

This portfolio delivered a near-48 per cent gain in its best year. In its worst year, it lost over 36 per cent. At the end of the 12-year period it ended up at ₹3.67 lakh, earning a CAGR of 11.44 per cent. This is quite a decent return for a balanced portfolio.

However, setting the asset allocation at the beginning and not intervening afterwards, led to your equity allocation climbing as high as 75 per cent in 2007. This set you up for a 51 per cent market crash next year. Consequently, the peak portfolio value of ₹3.97 lakh which you reached in 2007 itself, diminished to ₹3.6 lakh by the end of 2011. But the positive thing about not rebalancing was that you didn’t have to track this portfolio or rejig it. This meant paying zero capital gains tax.

Annual rebalancing

In growing economies like India, equities outperform other assets in the long run. Therefore, any portfolio which starts out with an equity allocation, if left to its own devices, gets progressively riskier over time. This is why rebalancing is necessary.

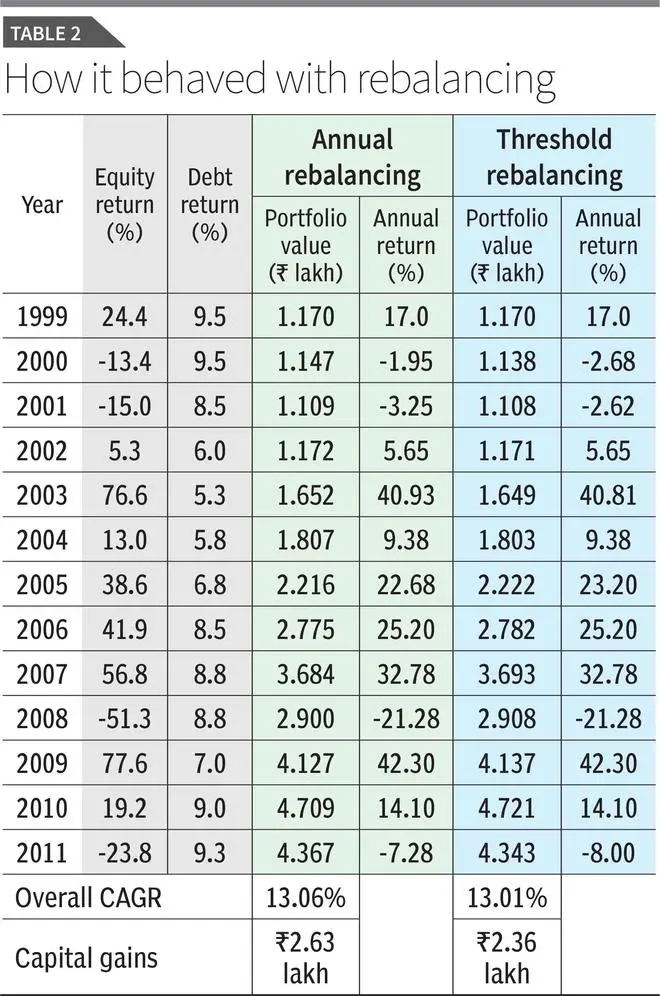

But a key decision to make is how often you should do this. Some experts suggest half-yearly rebalancing, but this takes up time and leads to portfolio churn. We experimented with annual rebalancing and it worked quite well. See Table 2 for details.

Starting with a 50-50 portfolio of ₹1 lakh in 1999 and taking stock at the end of each year, we found that equity weights overshot the set proportion of 50 per cent in eight of the 12 years, calling for book profits. Debt weights shot up in the remaining years and needed correction.

Tracing the portfolio value in this case point to a much smoother journey for the investor. The difference between the best and worst year was far less than in the first strategy. The best year generated a 42 per cent gain, while the worst year saw a 21 per cent loss. This would have made it behaviourally easier for the investor to stay the course with her investments.

The portfolio value also managed a steady climb over the 12 years instead of a yo-yo journey. The ₹1 lakh portfolio was worth ₹4.36 lakh at the end of 12 years, working out to a CAGR of 13.06 per cent. This beat the 11.4 per cent return without rebalancing.

The annual exercise of reviewing and rebalancing the portfolio required the investor to book profits on his equity holdings in eight years and on debt four times. This generated capital gains of ₹2.63 lakh over 12 years, which were reinvested.

Assuming a 12.5 per cent tax on equity gains and 30 per cent on debt gains, the total capital gains tax outgo was about ₹51,800 (less than the returns made from rebalancing). Here, we have not considered the ₹1 lakh a year exemption on equity gains or the impact of grandfathering.

Threshold rebalancing

Checking your portfolio and correcting its allocations every year, no doubt, delivers good results. But it does require effort and churn. Is there any way you can simplify this? Can you stop selling stocks or bonds on minor deviations and only do it in the case of major ones?

We ran a third strategy where the investor checks her portfolio at the end of every year, but rebalances it only if an asset shoots past its planned allocation by over 5 percentage points. Rebalancing was done only when equity or debt exceeds a 55 per cent weight in the portfolio.

Running this scenario, we found that the investor had to rebalance only in seven out of 12 years. The best and worst years on this strategy were almost identical to annual rebalancing. The investor ended up with a portfolio worth ₹4.34 lakh, ₹2,000 less than the annual rebalancing one. The CAGR worked out to 13.01 per cent. See Table 2.

But thanks to less churn, the capital gains incurred on this strategy was ₹2.36 lakh, much less than the ₹2.63 lakh on annual rebalancing. The capital gains tax outgo would be a lower ₹46,030.

The final lessons from this exercise are:

* Asset allocation with rebalancing works very well to reduce risk and lift returns

* Don’t worry about taxes when rebalancing. Benefits outweigh costs

* Rebalance only when asset weights exceed a threshold and not annually

The author is a Contributing Editor

Published on November 29, 2025